Feeding the Coastal Masses, A.D. 550

February 2017

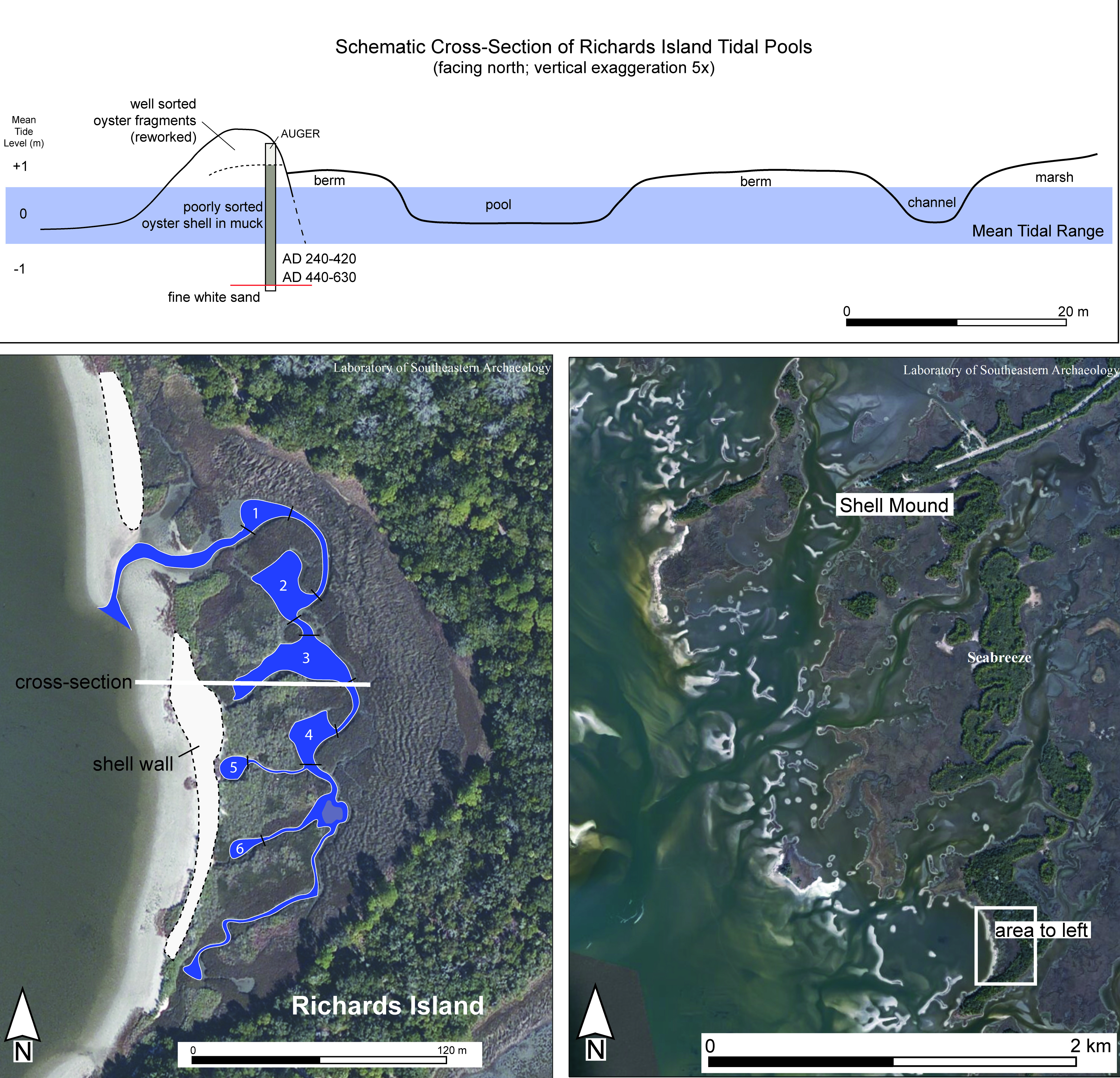

About 1,500 years ago on the northern Gulf Coast of Florida, Native Americans built the infrastructure to harvest large numbers of fish to supply periodic gatherings of people at nearby civic-ceremonial centers. A massive fish trap at Richards Island is among the recent findings of the Lower Suwannee Archaeological Survey (LSAS), an ongoing collaboration between University of Florida archaeologists and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The overarching research objective of the LSAS is to document human perception and response to sea-level rise over the past 5,000 years, but it also provides opportunities for graduate students to pursue various lines of research. This new discovery bears relevance to a variety of research questions, and it is the first such trap to be documented on the northern Gulf coast.

We owe this discovery to a seasonal resident of the town of Cedar Key, Mr. Ed Allen, who recognized the unusual configuration of impounded tidal pools on one of his many kayak trips along the coast. The oyster seawall that impounds multiple pools and connecting channels bears resemblance to storm surge deposits, but radiometric dating and other evidence shows it to be anthropogenic, that is, emplaced by people, around A.D. 550.

The motive for expending so much effort to catch fish can be found not in the demands of daily living, but rather in ritual gatherings at places like Shell Mound, 2 km north of the fish trap. Local communities hosted visitors from across the region at Shell Mound for feasts that required not only lots of fish, but oysters, other shellfish, deer, birds, turtles, and more. It also required the digging of massive pits and crafting of big pots for processing food, as well as an assemblage of serving vessels to distribute the bounty. Graduate students and colleagues are working to document what we call the “ritual economy” of Shell Mound: Meggan Blessing is identifying the vertebrate fauna, as is Josh Goodwin, who is focusing on a large assemblage of wading birds; Jessi Jenkins has documented evidence for oyster mariculture; Anthony Boucher is calculating the volume of pit digging and terraforming; and Terry Barbour, along with undergraduate student Megan Lisle, is reconstructing the assemblage of large pots that were evidently made, used, and broken in the context of gatherings. Ginessa Mahar’s ongoing work on mass capture of fish adds deeper context to Shell Mound feasts, and Mark Donop is providing better insight on the mortuary practices at nearby Palmetto Mound, for which gatherings were likely held.

As ritualized activities, gatherings and feasts at Shell Mound must have been tied to a ritual calendar. We are testing the hypothesis that these activities took place during summer solstices, around June 21. We have good reason to suspect a summer schedule: for millennia local residents had to deal with rising sea and one of their strategies was to relocate landward to the raised elevations of Ice Age dunes in the region. It just so happens that prevailing winds that created these dunes came from the southwest, in the direction of the setting winter solstice sun, which pushed sand to the northeast, in the direction of the rising summer solstice sun. Recognizing this orientation, coastal dwellers may have been engaged in a form of geomancy, that is, divining futures from “natural” patterns on the ground. This is one of the more recent explanations for why Stonehenge was sited where it is: bedrock just below the surface is scarred with periglacial fissures that are oriented to the solstices. By relocating cemeteries vulnerable to sea-level rise to dunes on the Gulf coast, the dead led the living into the future, cued by a celestial body whose regular movements mitigated the uncertainty of changes in sea level.

The permanence of infrastructure like Shell Mound and the fish trap eventually became a liability for people whose tradition was to relocate back from the coast as water rose. By A.D. 700 Shell Mound and similar civic-ceremonial centers on the coast were abandoned. The networks of affiliation that led to such large gatherings afforded options for relocating, and many people seem to have moved to places like north-central Florida. They returned to the coast occasionally to continue to honor their ancestors with gifts of pottery and other objects. But they did not again engage in such intensive fishing and food preparation, owing perhaps to lessons learned about the limits to coastal settlement. Our own future with sea-level rise may not be all that different.

Funding for the Lower Suwannee Archaeological Survey is provided by the Hyatt and Cici Endowment for Florida Archaeology.