“Freedom Fort: In eighteenth-century Spanish Florida, a militia composed of formerly enslaved Africans fought for their liberty”

Archaeology magazine has featured work conducted by some UF archeologists: James Davidson (professor), Liz Ibarrola (alumna), and Kathleen Deagan (Florida Museum of Natural History)

“‘We’re particularly interested in the domestic side of things,’ says Ibarrola. ‘What did the conversion to Catholicism look like? What did people’s daily life look like and how did it change when they moved to this place?'”

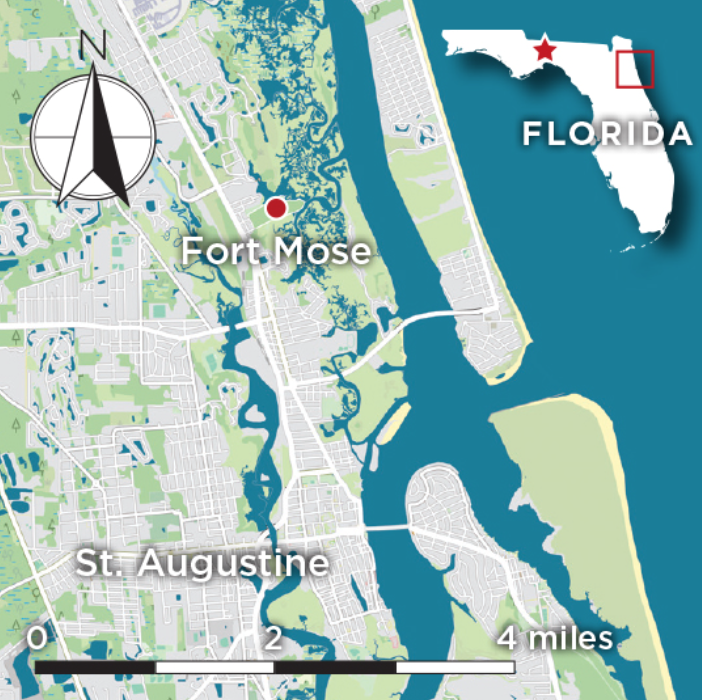

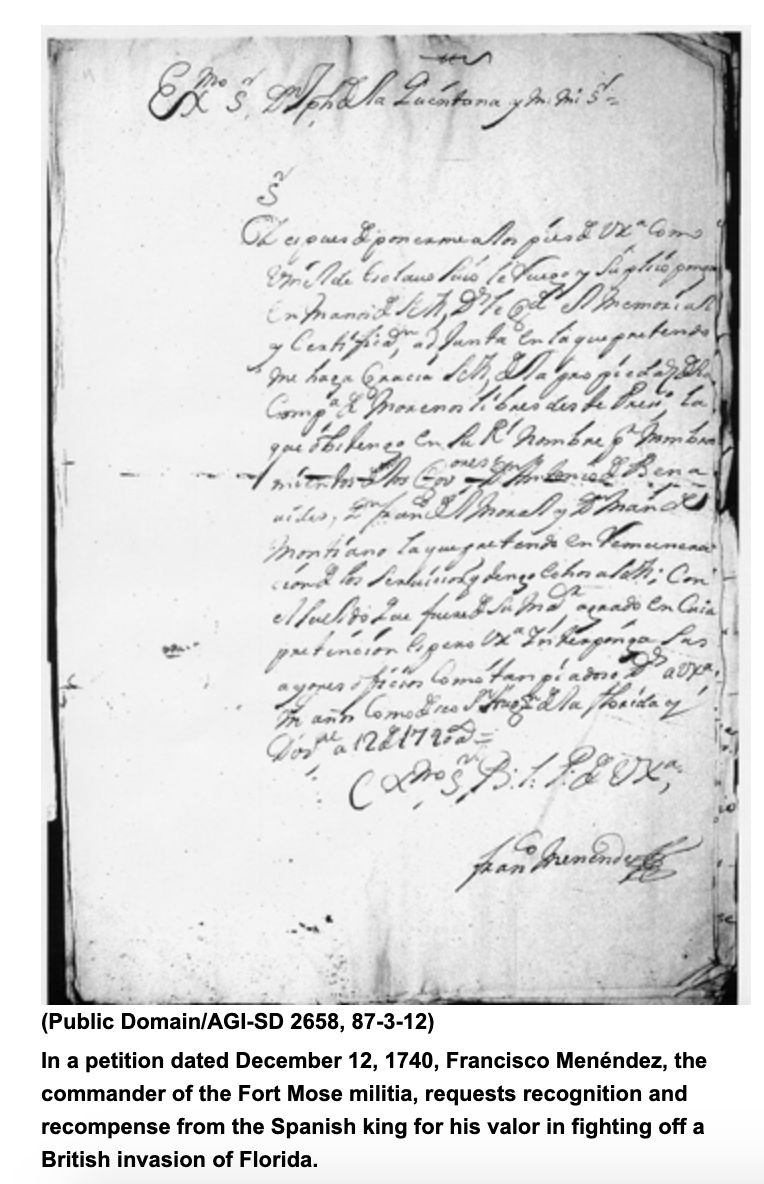

“The Fort Mose militia took its role as defenders of the colony extremely seriously. In a declaration to the king of Spain, its members pledged to be “the most cruel enemies of the English” and to put their lives on the line and spill their “last drop of blood in defense of the Great Crown of Spain and the Holy Faith.” They wouldn’t have to wait long to make good on their pledge. In September 1739, one of the largest rebellions by enslaved people in North American colonial history broke out near the Stono River in South Carolina, leading to the death of 25 colonists before it was crushed. The English blamed the Spanish promise of freedom for inspiring the rebels. A broader conflict between Britain and Spain, the War of Jenkins’ Ear, broke out soon after, and, early in 1740, James Oglethorpe, governor of the English colony of Georgia, attacked Florida and overwhelmed Fort Mose. The Black militia retreated to the Castillo de San Marcos, the Spanish fort in St. Augustine. They mounted a surprise attack in June 1740, reclaiming Fort Mose in a ruthless battle that came to be known as Bloody Mose. Their fort, however, had been destroyed, and the militia would remain in St. Augustine for the next 12 years.”